For the photographer, time is the motive and time is the limit. She seeks to fix a perception of a scene or a person in an instant and hold that instant open. But to frame that scene is to rend the fabric of time, to reduce the rich complexity of context and create an artifact where there had been an unfolding event or a living presence. This strange confinement becomes most obvious with the portrait. The photograph can capture only appearances, wonderful in their particularity but deceptive in their pretension to say anything at all about a person except: she looked like this at just this time.

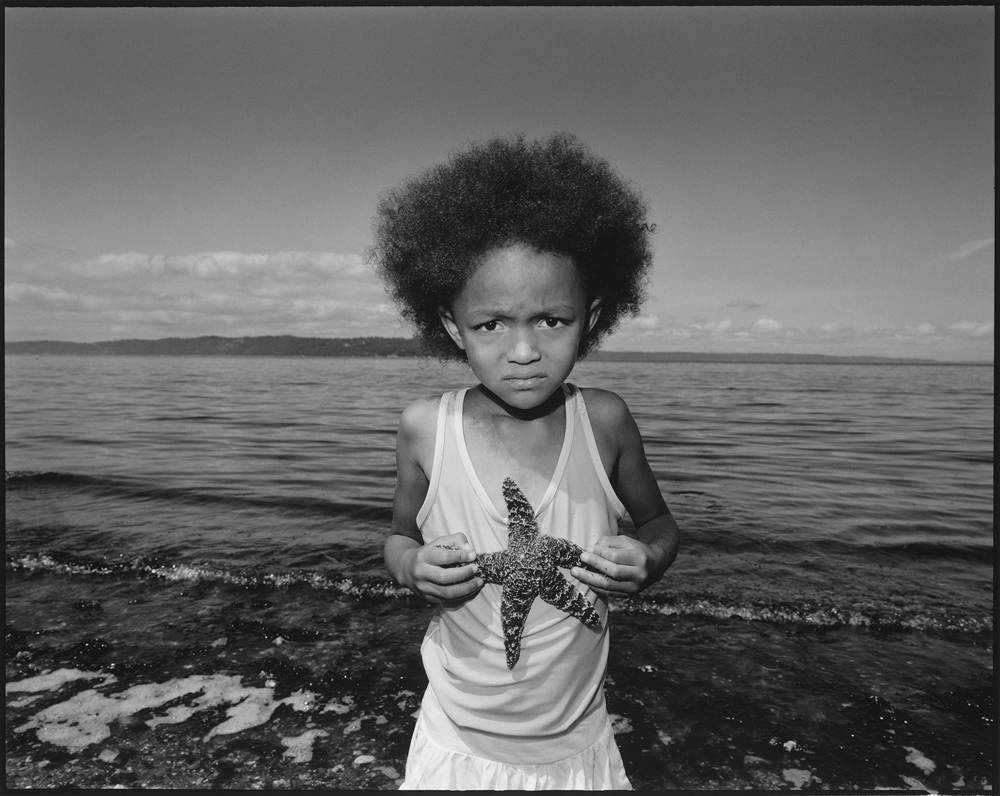

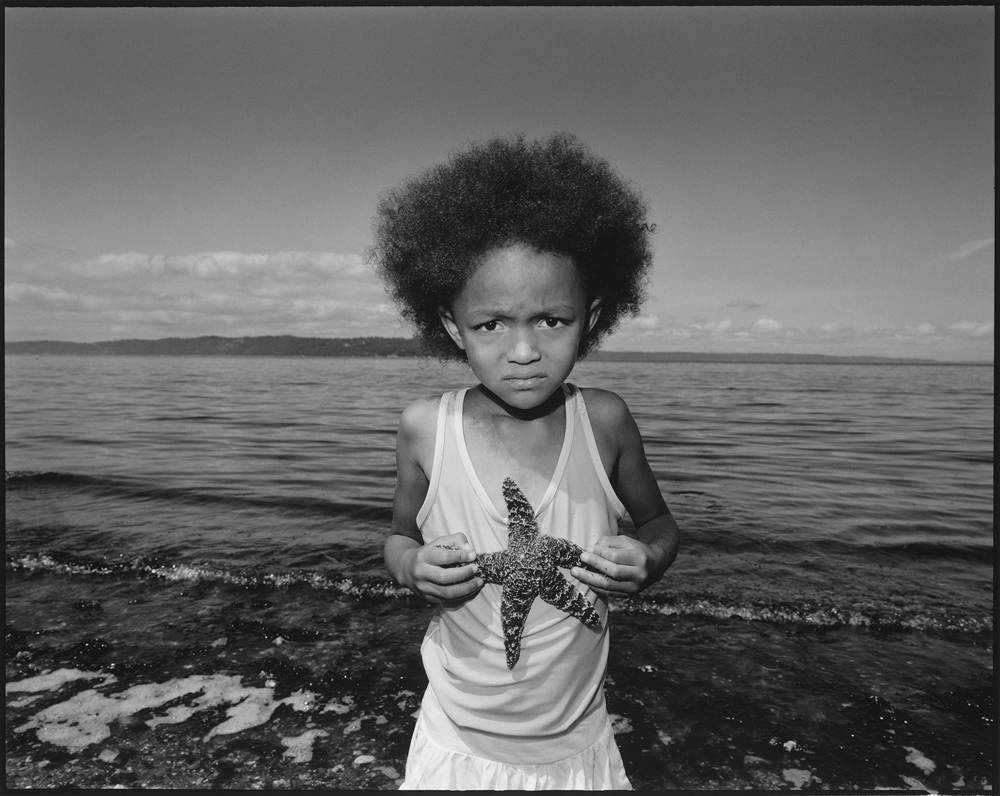

When the late Mary Ellen Mark first met Tiny, she must have sensed that it would be her responsibility to overcome this limit and make of the photograph something more than a pale inventory of two dimensions. Tiny’s trajectory would occupy the rest of Mark’s creative life, some 30 years off and on, until her untimely death in 2015. She left us a novel in pictures, the expanding domestic record of one life, as it ramifies through partners, children, and their partners. Streetwise is the name of the original photo project and the film made with her husband, Martin Bell. It followed a group of homeless children living on the streets of Seattle, a rootless reality in the heart of Reagan-era America. But Mark kept coming back, taking more pictures and adding chapters to a story that could have ended as a single prick to liberal conscience. Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, on view at Aperture Gallery (May 26-June 30), is an overview of the entire relationship curated by Mark in collaboration with her longtime friend and editor Melissa Harris. The project has pride of place on a short list of visual engagements with the mystery of lived time, including filmmaker Michael Apted’s 7 Up series, Andrea Modica’s photographs of Barbara, and Nicholas Nixon’s periodic portraits of the Brown Sisters. “Mary Ellen’s commitment to Tiny as a real and complex human being, living a fraught life, fascinated me,” says Harris. “It was an ongoing relation between two fierce and combative people, and I love the parity of it.”

In contrast, Harris also curated a selection of 40 of Mark’s individual portraits, spanning her career, at Howard Greenberg Gallery (May 5- June 19). Seen in the context of Streetwise, their striking feature is the pressure we sense on the photographer to find a way past appearances, or through them, to portray some inner aspect of the subject in a single image. She did it, according to Harris, by responding to her subjects’ sense of self-possession. Harris calls it “attitude” and uses the word as a title for the exhibition. The best-known example is the portrait of the adolescent Tiny in black dress, hat, and veil, a survivor not afraid to imagine herself differently. Her portrait of Mother Teresa in India likewise shows not a saintly caregiver but a worker among the dying whom nothing can deter. “These are not epic symbols but individual human beings,” adds Harris. “Their is-ness, the force of their being, shines through.”